ENQUIRE ABOUT A MANDARIN DRAKE

ADD TO WISHLIST

ADD TO COMPARE

Signed and dated l.r.: S:Stone 1788, inscribed in pen and brown ink verso: Sam: Lysons., watercolour with gum arabic and touches of bodycolour on wove paper

37 x 30 cm.; 14 1⁄2 x 11 3⁄4 inches

Provenance

Probably Samuel Lysons, FSA (1763-1819);

Henry Rogers Broughton, 2nd Baron Fairhaven (1900-1973);

By family descent;

Sotheby’s, London, sale of the Library of Henry Rogers Broughton, 2nd Baron Fairhaven, Part II, 29 November 2022, lot 478

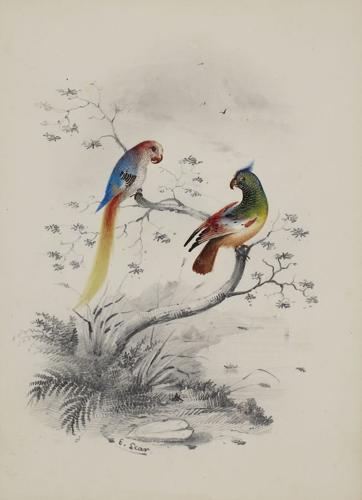

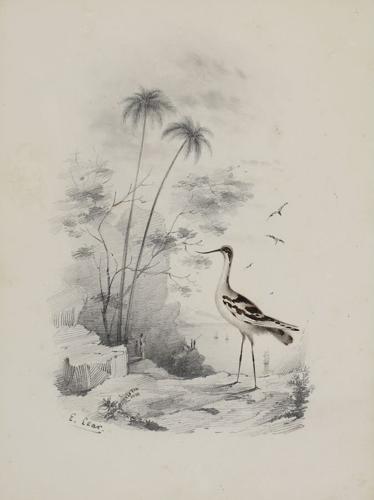

Sarah Stone was the first female British painter of birds and animals to achieve professional recognition. Her drawings of birds are a highly important visual record of the specimens held in collections in late eighteenth-century England, and include some of specimens collected on the voyages of Captain Cook.

The Mandarin drake from China (Aix galericulata) is shown raising the fan-shaped, cinnamon coloured innermost pair of secondary wings on his back like sails in a courting gesture. Stone evidently admired the Mandarin duck as she made several versions of the present drawing. One is in the Natural History Museum, London (see Christine Jackson, Sarah Stone Natural Curiosities from the New Worlds, 1998, p. 113, NHML no. 54, ill. Pl. 54 p. 81). Another, smaller version dated 1781 (in poor condition) was sold at Bonhams, London, 12 October 2022, lot 3.

Stone was employed when she was still in her mid-teens to draw the objects in the Holophusican or Leverian Museum, a major cultural institution of the day housed in the former royal palace of Leicester House. She was to work there for nearly thirty years. Its owner, Sir Ashton Lever (1729-1788) commissioned her by 1777 to record specimens and ethnographic material brought back by British expeditions to Australia, the Americas, Africa and the Far East.

For financial reasons, Lever had to dispose of his collection in the 1780s, by lottery. Before doing so, he apparently commissioned Sarah Stone to depict the birds, ethnography and antiquities. From January to March 1784 Lever exhibited Stone’s work, advertising the show as:

‘a large Room of Transparent Drawings from the most curious specimens in the collection, consisting of above one thousand different articles, executed by Miss Stone, a young lady who is allowed by all Artists to have succeeded in the effort beyond imagination. These will continue to be open for the inspection of the public until they are removed into the country. Admittance HALF-A-CROWN each...Good fires in all the galleries.’ (See C. Jackson, ibid, p. 22).

Lever kept Stone’s drawings after the exhibition. The Leverian Museum continued to grow under new ownership through the 1780s and 1790s, and Stone continued to work there.

Stone drew items from other private collections and the British Museum. As most of the actual specimens have not survived, her drawings are a vital record of contemporary collections, few of which produced catalogues, and give valuable insight into the collecting practises of Enlightenment museums.

Sarah’s father James Stone was a fan painter, and it is likely that Sarah assisted him. As a child she was taught to make her own pigments using natural ingredients. She practised working in bodycolour as well as watercolour as a child, and the exquisite brushwork which can be seen in the drawing of the feathers of the duck demonstrates her skill at using bodycolour and gum arabic to intensify the colours.

Stone exhibited at the Royal Academy, London in 1781, 1785 and 1786. She exhibited paintings of birds at the Society of Artists in 1791. She married John Langdale Smith, a midshipman, on 8 September 1789; she exhibited as a ‘painter’ before her marriage and in her married name as an ‘Honorary Exhibitor.’ She painted less after her marriage, predominately drawing live birds which her husband, also an artist, brought back from his travels.

Stone was twenty seven when she married. A, daughter Eliza, who probably died in infancy, was baptised in September 1792 at St John the Evangelist, Westminster. A son, Henry Stone Smith (1795-1881) was baptised in the same church in March 1795. The family has a note by him recording a bird ‘Topial’, probably a troupial, which was brought back from the West Indies by his father and lived with the family (see C. Jackson, ibid, p. 30).

Further examples of Stone’s watercolours can be found in the British Museum, the Natural History Museum, London, the Art Gallery of Ontario, the National Gallery of Australia, the National Library of Australia, the State Library of New South Wales, the Yale Center for British Art, the Getty, the Bernice Pauahi Bishop Museum, Honolulu, Hawaii and the Alexander Turnbull Library, New Zealand.

Paris Spies-Gans has written about Stone’s participation in the imperial project in Paul Mellon Centre Notes, No. 20, ‘Colonialism in the Photographic Archive’, January 2022, pp. 11-12).

Samuel Lysons, FSA (1763-1819)

The inscription on the reverse of the drawing suggests it was owned by Samuel Lysons, FSA. Lysons was a Gloucestershire antiquarian, engraver and archaeologist, whose interests centred on Roman archaeology and mosaics and Gloucestershire church architecture. He was the Director of the Society of Antiquaries from 1798 to 1809. He illustrated his brother Daniel Lysons’ Environs of London, and the two collaborated on Magna Britannia, Being a Concise Topographical Account of the Several Counties of Great Britain, published in several volumes from 1806 to 1822.

Henry Rogers Broughton (1900-1973)

Henry Rogers Broughton succeeded his older brother Urban Huttlestone Broughton as the 2nd Lord Fairhaven in 1966. He was born in the United States and educated at Harrow, before joining the Royal Horse Guards in 1920. Their father, English emigré Urban Broughton (1857-1929), had a successful career building sewerage systems in the USA in the 1890s and married Carla Leland Rogers (1867-1939). She was the daughter of the wealthy oil and railroad tycoon Henry Huttlestone Rogers (184-1909). In 1912 the family moved to London. The title Lord Fairhaven was awarded to Urban for his political activities, but he died before he could use it and his eldest son Huttlestone became the first Baron Fairhaven.

Both brothers were great collectors and Henry put together one of the largest twentieth-century collections of depictions of natural history. He left a large bequest of one hundred and twenty flower paintings, over nine hundred watercolours and drawings and forty-four volumes of drawings by botanical artists such as Redouté and Ehret to the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge (the Broughton Bequest). The brothers’ home, Angelsey Abbey near Cambridge, with its large natural history collection, was left to the National Trust in 1966.