Edward Lear

- Years

- 1812 - 1888

- Country

- United Kingdom

- Available items

- 11

- Sold items

- 14

Biography

Click here for the latest catalogue

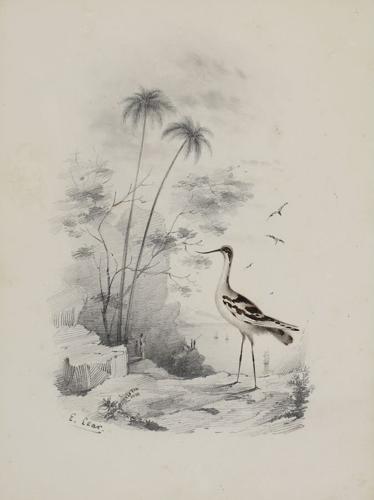

For many years after his death in 1888, Edward Lear’s reputation rested on his extraordinary poetry. Featuring magical creatures such as the Dong with a luminous nose, the Pobble who lost his toes, the pair of sailors in the beautiful pea-green boat and his brilliant limericks, his work earned him his place in Poets’ Corner in Westminster Abbey. Today, however, we recognise his artistic achievements as well, and over the years the many exhibitions of his ornithological art and landscapes have cemented his well-deserved reputation as an artist of the first rank.

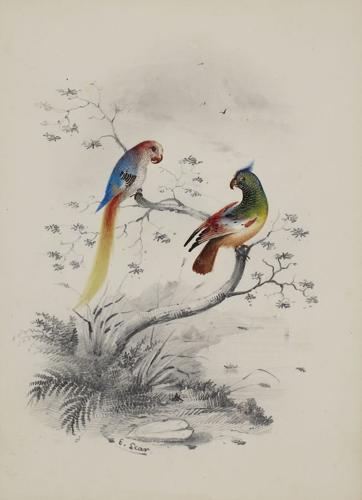

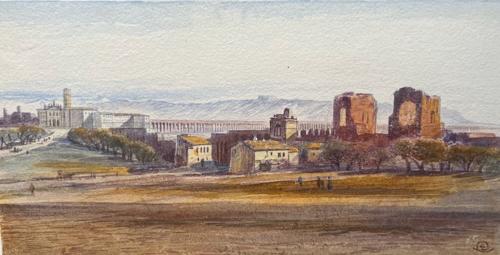

Lear’s quirky early drawings of birds exhibit the humour found in his verse. In 1837, with financial assistance from his patron, Lord Derby (1775 -1851), the twenty-five-year-old Lear set off for Rome. He remained based there for the following decade, a formative phase of his artistic development. The influence of the artist James Duffield Harding (1798 – 1863), whose drawing manuals Lear owned, can be seen in his pencil and chalk drawings. During the summer months, Lear would travel to other parts of Italy. In the winter, he would return to Rome and sell his work to British residents and visitors to the city.

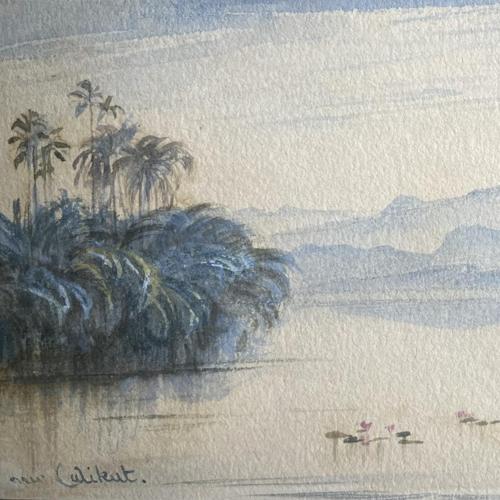

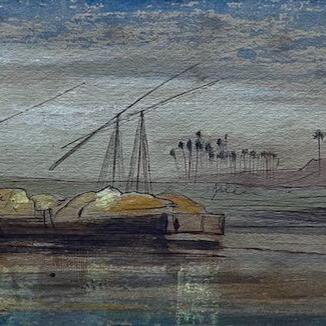

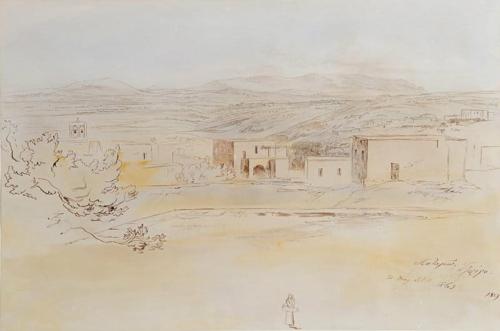

Lear’s travel watercolours, often extensively inscribed, frequently with nonsense writing, which he used extensively for reference for his oils and more finished watercolours are very popular today. Lear made a clear distinction between them and his more finished studio work. While they are unsigned, they are invariably dated and numbered, often with the time of execution recorded, as well as detailed colour notes and other inscriptions.

Lear’s style of travel was leisurely, but he concentrated intensely and drew quickly during his working periods, usually first thing in the morning and in the evening. Some works were drawn in a matter of minutes, others, usually on larger sheets, would take him a few hours of an evening. He numbered the drawings in sequence as he went along. He added colour washes once he was back at home, following his colour notes made on the spot, and pen and ink inscriptions are frequently superimposed over the original pencil comments. Lear’s landscapes are invariably topographically accurate, but his poetic handling, which transcends representation, makes his work so appealing. His phrase ‘poetical topography’ aptly describes his watercolours and perhaps underscores the noticeable confidence of his working drawings.

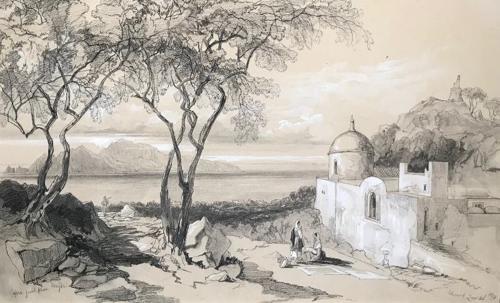

Lear greatly admired Lord Byron (1788 - 1824) as a child, as a result of which he had been fascinated by Greece from an early age. He wrote to his friend Chichester Fortescue before he first set out for Greece that, ‘I cannot but think that Greece has been most imperfectly illustrated… the vast yet beautifully simple sweeping lines of the hills have hardly been represented I fancy – nor the primitive dry foregrounds of Elgin marble peasants &c. What do you think of a huge work (if I can do all Greece)?’ (26.viii.48 MS, Somerset Record Office, Taunton). Lear travelled with Charles Church on his first trip to Greece in June and July 1848. While he travelled all over Greece from 1848 – 1864, drawing extensively, he never made a comprehensive record of the entire country. By 1853, Lear was on his way to Egypt.

Lear’s last trip (1873 - 1875) was to India, at the invitation of his friend and patron, Lord Northbrook (1826 – 1904), who served as Viceroy from 1872 to 1876. This was the longest journey Lear ever undertook and he was overwhelmed by the colour and vitality of everything he saw in India. In 1870, Lear built a house in San Remo on the Italian Riviera, where he lived with Giorgio, his devoted manservant and travelling companion, after his return from India until his death in 1888. It was in this period that he wrote his greatest nonsense poetry and conceived of the Dong, the Pobble, the Jumblies and the Yonghy-Bonghy-Bò.